As at January 2019, I have begun consolidating all of my 16th c Irish research onto a stand-alone blog: Saffron Cloth, Renaissance Irish Clothing Resources.

My dabbling in 16th century Irish clothing started with my Livery Project on 16th Century Irish Attire in 2011. Compared with neighbouring regions in this timeframe, relatively little is known about the Irish clothing of this time, there are very few extant pieces, and comparatively few people recreate it. I am drawn to this style of clothing because it is unique, a little bit odd, colourful and different to most things worn in Lochac. I am also drawn to Irish clothing because it links to my SCA name, Ceara Shionnach, which is Irish Gaelic.

There are two main types of armour-type jackets that are depicted in extant images from the type – the ionar (Figure 1) and a second kind (Figures 2-4) (the latter I have not yet come across a name for). It is the second kind of jacket that interested me.

Figure 1: Detail from Irish men and women, by Lucas d’Heere, circa 1575. The man in the foreground is wearing a red ionar jacket with fringing contrasts. Image sourced from Irish Archaeology online.

The clearest images of this jacket are seen in woodcuts by John Derrick called The Image of Irelande, with a Discoverie of Woodkarne, which was English propaganda against the Irish from 1581. Digital images of the full set of plates from this publication are available for viewing on Wikipedia.

Despite the obvious similarities, there are also slight differences between the jackets worn in the follow three Figures. A comparison summary follows:

Common Features

- Where visible, the neckline is high and round at the back and a plunging v-neck (going almost to the skirts), with contrast edging, at the front;

- A skirt of tubular pleats around the true-waist;

- Tight-fitted, full-lengthed sleeves with contrasting cuff edges;

- Billowing leine sleeves hanging from the tight-fitting sleeves;

- A secondary, short skirt under the tubular-pleated skirt that only just covers the crotch and buttocks; and

- There does not appear to be much decoration (e.g. there is no embroidery or obvious decorative trimming other than small areas of possible contrasting fabric at the cuffs).

Apparent Differences

- Figures 2 and 3 have slashing visible on the sleeve head whereas Figure 3 has no slashing;

- The longer, secondary skirt in Figure 2 is more obviously ‘free flowing material’ than the other two figures, and looks to me to be the same fabric as the billowing sleeves. This suggests to me that the secondary skirt in this image is part of the leine (under shirt) other than part of the jacket;

- The skirts of Figures 3 and 4 appear to be made of a stiffer fabric, and also appear to be made of the same fabric as the rest of the jacket;

- The tubular-pleated skirt of Figure 2 is approximately 1/3rd the length of the secondary skirt, whereas the tubular-pleated skirts of Figures 3 and 4 appear shorter (looking much more like Elizabethan ruffs) and are approximately 1/4 the length of the secondary skirt; and

- Figures 3 and 4 have a bold, thick contrast around the v-neckline whereas Figure 1 does not have any obvious contrast on the neckline (granted, we can’t see the front of this image).

Figure 2: Detail from Plate 7 of John Derrick’s The Image of Irelande (1581), depicting the Irish messenger Donolle Obreane. Image sourced from Wikipedia.

Figure 3: Detail from Plate 1 of John Derrick’s The Image of Irelande (1581), depicting an Irish soldier holding a battle-axe. Image sourced from Wikipedia.

Figure 4: Detail from Plate 3 of John Derrick’s The Image of Irelande (1581), depicting an Irish bard entertaining the chief of the Mac Sweynes at a feast in the woods. Image sourced from Wikipedia.

It’s important to note that, because these woodcuts by John Derrick are English propaganda, they may not accurately depict clothing worn by the Irish at the time. It is possible that features of their attire were exaggerated to make them appear more ‘wild and uncouth’ than they were.

However, there are elements of clothing in these woodcuts that are clearly likely to be accurate examples of 16th century Irish attire. For example, in plates 2 and 4 there are women wearing ‘cheese mould hats’ and in plates 3 and 11 there are Irish men wearing distinctly Irish mantles.

There are also three other pieces of evidence that loosely support various elements observed in the jackets from Derrick’s woodcuts, depicted below in Figures 5-7. The first image, Figure 5, depicts ‘A fresco of Irish archers painted on a wall of Knockmoy Abbey, Co. Galway, Ire. Early Tudor Period (1485-1603)’. The archer on the left, whilst not wearing the same outfit observed in Figures 2-4, has some striking similarities obvious: a short, pleated skirt to the crotch/buttocks and hanging from the true waist with tight-fitted, full-lengthed sleeves.

Figure 5: A fresco of Irish archers painted on a wall of Knockmoy Abbey, Co. Galway, Ireland. Early Tudor Period (1485-1603). Image sourced from Pinterest.

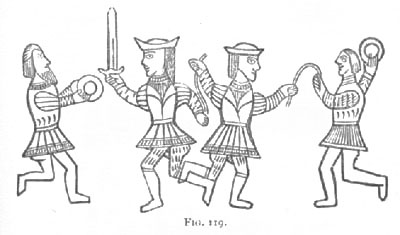

Figure 6 again depicts Irishmen who are not wearing the jacket from Derrick’s woodcuts. It does, however, depict Irishment from approximately the 14th-15th century with similar jacket features to Derrick’s woodcuts. Notably, the necklines are different but still have the overall v-neck look and the skirts appear to be pleated and hanging to the crotch/buttocks.

Figure 6: A group on ancient engraved book-cover of bone, showing costume: one with cymbals; and all engaged in some kind of dance. 14th or 15th century. Image is Figure 119 from A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland by P.W. Joyce 1906.

Figure 7 depicts a fragment of an extant jacket that is a part of the Kilcommon Costume. It is dated to Ireland in the late 16th or early 17th century. The jacket has a short, pleated skirt hanging from approximately from the true waist. These pleats, however, do not appear to be tubular like those in Derrick’s woodcuts.

Figure 7: The extant jacket from the Kilcommon Costume, 16th-17th century Ireland. Image sourced from Reconstructing History.

In summary, whilst it is entirely possible that the jackets observed in Derrick’s woodcuts are exaggerated Irish clothing rather than true depictions of clothing at the time, there are various elements within these outfits that are common to other, more reliable resources depicting Irish clothing around the time.

Initially, this project was thought up because I was unhappy with my heavy armour getup, I roughly sketched a design for a 16th century Irish armour outfit in April 2013. However, found it difficult to adapt the outfit for this purpose without sacrificing too much of the look. When I took up rapier in May 2014, it became obvious that this outfit would be more easily adapted to fencing rather than heavy combat, primarily because most of the armour in SCA fencing is fabric-based.

Figure 8: Rough sketch of my initial Irish 16th century jacket to wear for heavy combat in the SCA. Image drawn by Ceara Shionnach, April 2013.

As I have been unable to find any extant items for this jacket style, and no patterns, I decided to make my pattern from scratch. I started this process by making my first attempt at duct tape method for patterning. As shown in Figure 9, I donned a large plastic bag and had my friend Ginevra wrap my torso in bright pink duct tape (which I had lots spare of, thanks to the “generosity” of Count Stephen).

Figure 9: Ginevra wrapped me in duct tape to make the model for my pattern. Image of Ceara Shionnach by Ginevra Lucia di Namoraza 2014.

Next, I drew the seams, edges and neckline of the jacket onto the duct tape (whilst I was still wearing it) to mark out where my pattern pieces would like fall. I kept the v-neck shape from Figures 2-4, however, I raised where the neckline plunges to, making it more female and fencing appropriate. Once that was done, I cut the centre-front seam to get out of the duct tape model and trimmed the edges to match the pattern I had drawn.

I cut each of the seams, leaving me with four pattern pieces (two front and two back). I used scrap cotton fabric to trace the duct tape pattern pieces on to, and made a mock up of the bodice of the jacket. Using pins and a texta, I altered bits of the pattern to make it fit better, re-drafting the pattern 3 times before I was happy with it.

For the outside of my jacket, I used a bright green linen. The Irish were known for their bright colours and certainly had green dye available, and linen and wool were the most common fabrics available to them, so I felt it was an appropriate choice for my jacket. I decided to line the jacket with a red-brown linen, which would provide a contrast but not be too extreme (as I am often want to do – all the colours!). In order to make the jacket SCA fencing-legal, I interlined the jacket with a cotton-linen canvas. The canvas and linen were drop tested by Don Owain before construction began and, whilst neither fabric was puncture proof on their own, they were puncture proof when layered together. I machine-sewed the outer and inter-lining layers together before hand stitching the lining in using stab stitch.

Figure 10: Photo of the lining, which was hand-sewn in to the jacket using stab-stitch. Photo by Ceara Shionnach, 2014.

After the bodice of the jacket was together, I drafted some generic, full-lengthed, tight-fitting sleeves. To achieve the larger sleeve-cap observed in Figures 2 and 3, I made another sleeve cap that was 1.5 times wider around the arm than the original sleeve cap. I appliquéd some of the red-brown linen onto these sleeve caps to achieve the appearance of fake slashing. This was because I was concerned about real slashing being ripped by swords getting stuck in them whilst fencing. The sleeve caps were then pleated and sewn over the sleeve caps of the full sleeves, resulting in puffed and slashed sleeve caps. These sleeves are loose imitations of those observed in Figure 2.

Figure 11: The sleeve pattern and cap head with appliquéd fake slashing. Photo by Ceara Shionnach, 2014.

Figure 12: The sleeve cap was pleated and attached to the sleeve by hand. Photo by Ceara Shionnach, 2014.

I got the measurements of the skirts by measuring the skirts in Figure 2 and adapting those ratios to my own body size. The tubular-pleated skirt is just over 3 times my waist measurement, and is approximately one third the length of the secondary underskirt. As I needed to have the secondary skirt puncture-proof for fencing, I decided to go for the skirts as part of the jacket, as observed in Figures 3 and 4.

Figure 13: The tubular pleats are pinned to the secondary skirt and handsewn in. Photo by Ceara Shionnach, 2014.

Since finishing my jacket in October 2014, I have worn it three times and fenced in it twice. It is much easier to move in than my previous fencing jacket, which was restrictive in the arms, thicker (and thus hotter to wear!) and generally a bit uncomfortable to wear.

Figure 14: Me, wearing my jacket and fencing hood whilst in Innilgard. Photo by Fionnabhair inghean ui Mheadhdra.

I would still like to make an ‘onion hat’ (Figure 15), get some better tights to wear with it, find some fencing-appropriate (i.e. sport supportive) whilst still period shoes, and make an undershirt to wear with it to complete the outfit.

Figure 15: Detail of a female figure from Lucas de Heere’s watercolour of Irish as they stand accoutred being at the service of the late King Henry (ca 1575).

In the mean time, I can wear the jacket with my puncture-proof hood pinned down over the v-neck, and I can wear my ‘cheese mould hat’ as an Irish piece of headwear and my 16th century English black leather shoes to go with it when not fencing (Figure 16).

Figure 16: Me, wearing my new jacket for the first time at the Battle of Bottony Cross in the Barony of St Florian de la Riviere. Photo by Iglesia Delamere, October 2014.

References

Much of the context of this outfit (style, materials, colours, etc) were identified as I undertook my research project in 2011: Livery Project on 16th Century Irish Attire. There are many period references located on that blog page and the attached Word file of my project.

Image 1: http://irisharchaeology.ie/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Gaelic_clothing_Ireland.jpg

Image 2: Detail from Plate 7 of John Derrick’s The Image of Irelande (1581), depicting the Irish messenger Donolle Obreane. Image sourced from Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Image_of_Irelande,_with_a_Discoverie_of_Woodkarne

Image 3: Detail from Plate 1 of John Derrick’s The Image of Irelande (1581), depicting an Irish soldier holding a battle-axe. Image sourced from Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Image_of_Irelande,_with_a_Discoverie_of_Woodkarne

Image 4: Detail from Plate 3 of John Derrick’s The Image of Irelande (1581), depicting an Irish bard entertaining the chief of the Mac Sweynes at a feast in the woods. Image sourced from Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Image_of_Irelande,_with_a_Discoverie_of_Woodkarne

Image 5: A fresco of Irish archers painted on a wall of Knockmoy Abbey, Co. Galway, Ireland. Early Tudor Period (1485-1603). Image sourced from Pinterest: http://www.pinterest.com/pin/437341813788011507/

Figure 6: A group on ancient engraved book-cover of bone, showing costume: one with cymbals; and all engaged in some kind of dance. 14th or 15th century. Image is Figure 119 from A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland by P.W. Joyce 1906: http://www.libraryireland.com/SocialHistoryAncientIreland/Contents.php

FIG. 119. Group on ancient engraved book-cover of bone, showing costume: one with cymbals; and all engaged in some kind of dance. 14th or 15th century, (From Wilde’s Catalogue)

Figure 7: Reconstructing History – http://www.reconstructinghistory.com/

Figure 8: Drawn by Ceara Shionnach, April 2013.

Figure 9: Photo of Ceara Shionnach by Ginevra Lucia di Namoraza, 2014.

Figures 10-13: Photos by Ceara Shionnach, 2014.

Figure 14: Photo of Ceara Shionnach and Eva von Danzig by Fionnabhair inghean ui Mheadhdra, October 2014.

Figure 15: University Library of Ghent – http://adore.ugent.be/view/archive.ugent.be%3A1EEACAD8-B1E8-11DF-966C-0D0679F64438.

Figure 16: Photo of Ceara Shionnach at the Battle of Bottony Cross (first outing of the jacket), photo by Iglesia Delamere.