Pentathlon Entry 1 – Feature Item is Tin – March 2013

The following text is a summary of the Descartes Specials documentation from our first Pentathlon submission. I have focussed on my contributions to the entry on this page, however, the full documentation submitted for our first entry can be downloaded here: Tin Politarchopolis Pentathlon Entry 1.

Introduction

Our group received ‘tin’ as one of its items for the Pentathlon A&S challenge. After some initial research, the group decided to attempt tin-glazed earthenware. Specifically, the group made some tiles, a bowl, a plate, apothecary jars and a perfume bottle. In addition to using tin, we used (as encouraged to do so in the competition rules) oil (in the form of rose oil) and gold (in the form of gold-leafed bisketello). Therefore, in total, we used three of our five Pentathlon items for the first entry.

My contribution to this entry was:

· Designing the pattern for, and applying the tin glaze and pigments to, two tiles in a Spanish style of the sixteenth century;

· Designing the pattern for, and applying the tin glaze and pigments to, a bowl in an Italian style of the sixteenth century;

· Attempting to make a simple rose oil; and

· Contributing to the drafting/editing of the documentation.

Materials

Readily available modern clay and paintbrushes were used for practicality.

The tin glaze we used was a commercially available product but similar to what would have been used in period (Piccolpasso, 1557). The glaze recipe we used was:

Maiolica glaze ^05-04

Frit 3124 80 *

Kaolin 10

Ball clay 10

+ Tin oxide 10

* The frit covers what would have been a mix of silica, calcium oxide and lead, but in

this particular frit borax replaces the lead for safety.

Medieval pigments were used to colour the designs as follows:

Copper – green

Cobalt – blue

Red Iron – brown

Manganese – black

Yellow Ochre – red

Modern – yellow **

** We used a modern, commercial colourant to replicate yellow because of the toxicity of antimony which was commonly used during this period.

My Tiles

Tin glazing was introduced into Italy primarily through Spain and Northern Africa (LaTores, 2009). The term ‘maiolica’ was used in 15th-century Italy for lustrewares imported from Spain. The name was soon adopted for Italian-made lustre pottery copying Spanish examples, and during the 16th century its meaning shifted to include all tin-glazed earthenware (Victoria and Albert Museum, 2013b).

Decorative tiles were used on walls and floors in buildings. There are many examples of these across the SCA period, however, our team focussed on 15th-16th century Italian and Spanish tiles which have many extant pieces. My two tiles were based on two Spanish examples (figures below).

My tiles were shaped and fired by Els Piderman. Els made the tiles by rolling out the clay and cutting it into squares. The tiles were then fired to bisque (i.e. fired but not glazed) in the kiln.

I painted 5 layers of tin oxide onto my tiles after they had been fired to bisque. Tin oxide is a white base coat that is applied after the bisque but before the pigment is applied, and is used to make the glaze opaque. Tin glazes are evident in many extant, sixteenth century tiles located in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The Spanish examples of these tiles demonstrate the design impressed into the tile itself before the clay is originally fired to bisque. These impressions were made by carving the outline of the design for the tile into wood and pressing the clay into carved out design whilst shaping the tile (Somerset Brick and Tile Museum, 2012; van Lemmen, 2008). The grooves of the imprint were filled with white, wet (to a thick, liquid consistency) clay. Due to the inexperience of the team in ceramics, and the limited timeframe, it was not feasible to imprint the tiles and this step was not executed. Instead, the design was pencilled onto the tile on top of the tin oxide layer (to guide the application of the pigments in the absence of the imprints).

Spanish tiles, c1500-1550. “Tin-glazed earthenware with impressed designs, painted and glazed”

Victoria and Albert Museum, 2013 (museum number C.699-1923).

Toledo tile (Spanish), c1475-1500. “Tin-glazed earthenware”.

Victoria and Albert Museum, 2013 (museum number 2-1908).

Tile 1: Fox eating a goose

The design on my first tile is a fox eating a goose. The style of the pattern of the fox and goose is based on extant 16th century Spanish tiles located in the Victoria and Albert museum (see figures above). The animals were adapted from two images well pre-dating the time period of these tiles, however, I adapted the two earlier period images to try and match the style of the 16th century examples (see figures below). The reason for adapting the earlier period images was that I could not locate any 16th century examples of foxes (which are the primary heraldic charges on my personal device).

The pigments were painted over the tin oxide layer once it had dried. Blue, yellow and green pigments were used, similar to one of the period examples (figure above). Red pigment was used for the body of the fox. As evident in the two extant tiles used as inspiration for this piece, the background was left blank (i.e. with just the tin glaze coating).

The glazed and pigmented tile was fired in the kiln by Els. Once fired, the pigments change colour, as is evident in the figures above. All pigments except the red appear to have turned out okay. If there had been more time, the red could have been reapplied and re-fired to try and improve the result. However, it was not possible for this project due to time constraints.

Tile 2: Squirrel, acorns and oak leaves.

The design on tile 2 is a squirrel, some acorns and oak leaves (figures above). The style of the glazing of this tile is based on extant 16th century Spanish tiles located in the Victoria and Albert museum (figures above under ‘My Tiles’). The squirrel was adapted from an embroidered 16th century coif (figure below), keeping in mind the styles of the extant tiles. The acorns and oak leaves were adapted from a design on 16th century embroidered shirt (figure below). The squirrel motif was chosen as I am fond of the animal and it can be seen in many period designs, and, the oak leaves and acorns were chosen to appear with the squirrel in a layout similar to the rabbit tile example (i.e. a central beast with other, smaller motifs surrounding it whilst keeping a white background, figure of extant tile above under ‘My Tiles’).

Woman’s linen smock embroidered in purple silk and silver-gilt thread, Italian circa 1575-1600 (Wake, Annabelle, 2010).

The pigments were painted over the tin oxide layer once it had dried. Blue, yellow and green pigments were used, similar to the colouring in the extant examples of Spanish tiles (figures above in ‘My Tiles’). As is also evident in the extant tiles, the background was left blank (i.e. with just the tin oxide coating).

The glazed and pigmented tile was fired in the kiln by Els. Once fired, the pigments change colour, as is evident in the photos of my tile (figures above). The blue and yellow pigments turned out well. If there had been more time, the green could have been reapplied. However, it was not possible for this project due to strict timeframes.

Bowl: Fox and foliage.

The bowl was thrown on a potter’s wheel and fired by Els, and I glazed and painted the bowl with pigments.

Els painted 5 layers of tin oxide onto the tile after it had been fired to bisque (i.e. fired but not glazed). Tin oxide is a white base coat that is applied after the bisque but before the pigment is applied. It is used to make the glaze opaque, and tin oxide is evident in many extant, period bowls (including the period examples, pictured below). In 16th century Italy, white, opaque glazed pottery is termed ‘Maiolica’. The glaze contained tin-oxide which, at the time, was an expensive and imported substance that resulted in the pottery glazed with it more expensive than other similar pottery pieces. (McNab, 2000).

The design on bowl is a fox bordered by a repeated, multi-coloured foliage pattern. The style of the glazing of this tile is based on extant 16th century Italian bowls and dishes located in the Victoria and Albert museum (figures below). As can be seen in these extant pieces, there was a style of having a wide, ornate border with a central motif. This motif could be anything from a portrait, a beast (possibly the heraldic charge of the owner) or the heraldic device. Other similar tin-glazed dishes and bowls in the Victoria and Albert Museum depict detailed, scenic pictures of people, landscapes and beasts.

I adapted the fox used on this bowl from sources outline in the section on ‘Tile 1’. It represents my heraldic charge and was placed in the centre of the bowl (similar to the design in the bowl from Gubbio, pictured below). A thick border surrounds the fox, similar to the styles in the extant examples. The ornate foliage and block-colour border was inspired by the patterns on two 16th century Italian, tin-glazed drug jars. Whilst monotone could be used in pigmenting such dishes/bowls, there are examples of bright colours used in this period for dishes and bowls and other tin-glazed ceramics.

‘Dish’ from Deruta or Gubbio (Italy), circa 1500-1510.

Victoria and Albert Museum, 2013 (museum number 124-1896).

‘Dish’ from Gubbio (Italy), circa 1530-1540.

Victoria and Albert Museum, 2013 (museum number C.55-1923).

‘Dish’ from Faenza (Italy), circa 1490-1510.

Victoria and Albert Museum, 2013 (museum number 1767-1855).

‘Drug Jars’ from Faenza (Italy), circa 1550.

Victoria and Albert Museum, 2013 (museum number 107&A-1901).

‘Drug Jars’ from Faenza (Italy), circa 1550.

Victoria and Albert Museum, 2013 (museum number 107&A-1901).

The pigments were painted over the tin oxide layer once it had dried, following the pencilled in guidelines. Blue, yellow, green, red and black pigments were used (all of which are evident in the extant examples above.

The glazed and pigmented bowl was fired in the kiln by Els. Once fired, the pigments changed colour, as is evident by comparing the images of my bowl, above. The blue, yellow, green and black pigments have turned out well. If there had been more time, the red could have been reapplied to intensify the colour and have a more consistent coverage. However, it was not possible for this project due to strict timeframes.

Scented Oil: Rose oyle.

Oil (or oyle, as it is referred to in many 16th century recipes) is one of our five items to use in the Pentathlon.

224 grams (half a pound) of rosebuds were picked to make half of the quantity of the citrus blossom recipe (Anónimo, 16th century). This recipe was chosen as a first attempt at making scented oil due to the simplicity and speed in which it could be made. Citrus blossoms were substituted with roses because roses were more freely available at the time. There are many rose oil recipes found from the 16th century, some involving the scenting of an existing oil with roses (such as by Philbert Guibert Esq., 1639) and some involving the extraction and distillation of pure rose oil (such as by French, 1616-1657). The latter method takes the longest time to prepare.

Following the recipe, a mortar and pestle would have been used to crush the rose buds, however, I did not have one available. As such, she used a food processor (followed by crushing with the back of a spoon) to ensure that the rose buds were sufficiently pummelled. 15ml (half an ounce) of olive oil was added to the pummelled rose buds, however, this didn’t appear to be the correct amount to sufficiently wet the rose buds. Keeping in mind the instructions in Philbert Guibert Esquires (1639) rose recipe, I added enough olive oil to coat all of the plant matter. The mixture was left in a windowsill over an afternoon, a night, and a morning to allow the rose scent to infuse into the oil.

The oil was strained through linen to remove the plant matter from the oil.

The resulting, strained oil smells too strongly of olive oil, and not strong enough of rose. If time had permitted, I could have repeated the infusing process several times. This repeated infusing was employed in making rose oil in the 16th century. Using the lessons learned through this first attempt at making rose oil, another attempt shall be made for a future Pentathlon entry. Infused oils were used, for example, to scent water for washing hands.

The finished oil. It smelt a little too strongly of olive oil, and not strongly enough of roses. It would probably have held a scent better if I had time to repeat the infusion process many times.

I undertook this process as a basic introduction to scents, which I intend to look more into in the future. I am going to make an Elizabethan sweet bag, which were typically scented. Mistress Francesca brought me back some dried citrus blossoms from her recent trip to Europe and I am hoping to be able to use them in a scent for my sweet bag. They smell quite lovely and strongly in their bags.

Bibliography

In-text References

Adamson, Melitta Weiss, 2004. Food in Medieval Times. Greenwood Publishing Group.

Anónimo, 16th century Spain. Manual de mujeres, en el cual se contienen muchas y diversas recetas muy buenas. Translated to English and published by Medieval & Renaissance Material Culture. http://www.larsdatter.com/manual.htm, accessed 2013.

Charleston, Robert J.(edit.), 1990. World Ceramics; An Illustrated History. Hamlyn, London.

Coutts, Howard (2001). The Art of Ceramics: European Ceramic Design, 1500-1830. Yale University Press, Page 7. http://books.google.com.au/books?id=fRfIfV3Eq_sC&dq, accessed 2013.

French, John. 1616-1657. The art of distillation: The Oil commonly called the spirit of Roses. As published by Eleanour Sinclair Rohde in Rose Recipes 2008. http://books.google.com.au/books?id=cl89AAAAIAAJ&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false, accessed 2013.

LaTores, Alicia Marie, 2009. Luca della Robbia as Maiolica Producer: Artists and Artisans in Fifteenth-Century Florence.

McNab, Jessie, 2000. “Maiolica in the Renaissance”. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/maio/hd_maio.htm, accessed 2013).

Philbert Guibert Esq., 1639 Paris. Le medecin charitable (The Charitable Physitian): To make oyle of roses three ways. Translated to English by Jadwiga Zajaczkowa (in Making Medieval Style Scented Oils & Water). http://www.gallowglass.org/jadwiga/herbs/oil&water.html, accessed 2013.

Piccolpasso, Cipriano, 1557. “Li tre libri dell’arte del vasajo” (in English “The Three Books of the Potter’s Art”). http://archive.org/stream/itrelibridellar00minigoog#page/n39/mode/2up, accessed 2013.

Platt, Sir Hugh, 1602. Delightes of Ladies to adorne their Persons, Tables, Closets, and distillatories with Beauties, banquets, perfumes and waters. Reade, Practise, and Censure.

Scully, D. Eleanor & Scully, Terence Peter, 2002. Early French Cookery: Sources, History, Original Recipes and Modern Adaptions. University of Michigan Press.

Somerset Brick and Tile Museum, 2012. Medieval tile making (a video demonstration).

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ek6JxcbrXZM (accessed 2013)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iEFFG02lYOs (accessed 2013)

van Lemmen, Hans, 2008. Medieval Tiles. Osprey Publishing.

http://books.google.com.au/books?id=wToNn0ArHhMC&dq (accessed 2013)

Victoria and Albert Museum, 2013a. Search the collections, museum number 4901-1858 ‘Dish’ from Florence (Italy), circa 1450. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/, accessed 2013.

Victoria and Albert Museum, 2013b. A-Z of Ceramics – M is for Maiolica/Majolica. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/a/ceramics-m-is-for-maiolica-majolica/, accessed 2013.

Figure References

Tile 1

Victoria and Albert Museum, 2013. Search the collections, museum number C.699-1923 ‘Tile’ from Seville, Spain, circa 1500-1550. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/, accessed 2013.

Victoria and Albert Museum, 2013. Search the collections, museum number 2-1908 ‘Tile’ from Toledo, Spain, circa 1475-1500. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/, accessed 2013.

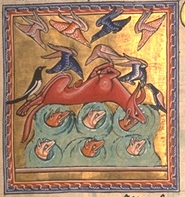

Mclaren, Colin and the Aberdeen University Library, 1995. The Aberdeen Bestiary, Folio 16R, England circa 1200. http://www.abdn.ac.uk/bestiary/translat/16r.hti, accessed 2013.

British Library Board, 2013. Luttrell Psalter – Psalm 15; Fox with goose. Published online by Topfoto. http://www.topfoto.co.uk/imageflows/preview/t=topfoto&f=BL022112, accessed 2013.

Tile 2

Victoria and Albert Museum, 2013. Search the collections, museum number C.699-1923 ‘Tile’ from Seville, Spain, circa 1500-1550. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/, accessed 2013.

Victoria and Albert Museum, 2013. Search the collections, museum number 2-1908 ‘Tile’ from Toledo, Spain, circa 1475-1500. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/, accessed 2013.

Victoria and Albert Museum, 2013. Search the collections, museum number T.32-1936 ‘Coif’ from Great Britain, circa 1600-1625. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/, accessed 2013.

Wake, Annabelle, 2010. Woman’s linen smock embroidered in purple silk and silver-gilt thread, Italian circa 1575-1600. http://realmofvenus.renaissanceitaly.net/workbox/extcam1.htm, accessed 2013.

Bowl

Victoria and Albert Museum, 2013. Search the collections, museum number 124-1896 ‘Dish’ from Deruta or Gubbio (Italy), circa 1500-1510. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/, accessed 2013.

Victoria and Albert Museum, 2013. Search the collections, museum number C.55-1923 ‘Dish’ from Gubbio (Italy), circa 1530-1540. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/, accessed 2013.

Victoria and Albert Museum, 2013. Search the collections, museum number 655-1884 ‘Bowl’ from Deruta (Italy), circa 1500. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/, accessed 2013.

Victoria and Albert Museum, 2013. Search the collections, museum number 1767-1855 ‘Dish’ from Faenza (Italy), circa 1490-1510. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/, accessed 2013.

Victoria and Albert Museum, 2013. Search the collections, museum number 107&A-1901 ‘Drug Jars’ from Faenza (Italy), circa 1550. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/, accessed 2013.